DGI2024 Report (1): What’s Holding Japan’s Social Sector Back from Doing Good? InsightsEssays: Civil Society in Japan

Posted on September 13, 2024

The Centre for Asian Philanthropy and Society (CAPS), a Hong Kong-based research and advisory organization, produces the biennial Doing Good Index, an in-depth comparative study of the social sector in Asia. Since 2020, the Japan NPO Center has collaborated with this study, gathering data from Japanese NPOs and experts.

The Doing Good Index studies the regulatory and societal environment in which private capital is directed toward doing good in Asia. Below are some findings from the 2024 edition of the report.

What’s Holding Japan’s Social Sector Back from Doing Good?

Examining Japan’s Performance on the 2024 Doing Good Index

What is the Doing Good Index?

The Doing Good Index studies the regulatory and societal environment in which private capital is directed toward doing good in Asia. Now in its fourth iteration, the Index identifies the policies and incentives that can drive private capital to the social sector and considers how stakeholders can build stronger, more trusting connections. It is an evidence-based resource for policymakers, philanthropists, academics and nonprofit leaders, offering in-depth insights and best practices to increase and enhance philanthropic giving.

The Index is based on data under four sub-indexes: Regulations, Tax and Fiscal Policy, Ecosystem and Procurement. Together, these indicators provide a picture of various factors impacting the supply and demand for private social investment in each economy. The findings are evidence-based, derived from survey data collected from 2,183 social delivery organizations and 140 experts across 17 economies, and supported by a network of partners and experts across Asia. After tabulation, the Index categorizes the economies into four clusters: Doing Well, Doing Better, Doing Okay and Not Doing Enough.

How does Japan perform on the Doing Good Index?

Japan’s performance has been stable in the last six years of the Doing Good Index, appearing in the second-highest cluster, Doing Better. While this indicates stability and the absence of major issues in the sector, it also highlights that the sector is potentially being held back from being even more effective and successful.

If Japan wants to move up into the Doing Well cluster (joining Singapore and Chinese Taipei), it will need to make improvements across the four sub-indexes. Below, we outline some of the areas where Japan performs strongly and where there are weaknesses.

Where Japan performs well

Japan’s regulatory system governing NPOs is relatively efficient in the context of Asia. NPOs require just two clearances in order to register as an organization, a process taking around two months, while the Asian average is three clearances and four months.

In terms of funding, 90% of Japanese NPOs receive funding from domestic sources, including individual donors and foundations. This is higher than the Asian average of 82%. 63% of Japanese NPOs receive government grants, compared to 45% of organizations in all of Asia. Japan’s NPOs also add to their funding through earning income from sales. 60% of all Japanese NPOs say they receive such income, compared with just 41% of organizations throughout Asia as a whole.

Where Japan can improve

Japan is a good performer on the Doing Good Index, but still has significant room for improvement in order to make the social sector stronger and more effective.

While domestic funding comprises almost half (47%) of the average Japanese NPO’s budget, most organizations (84%) say they believe overall levels of domestic funding in Japan are low. They point to issues such as insufficient tax incentives for donations, as well as limited trust in the social sector, as holding people back from donating.

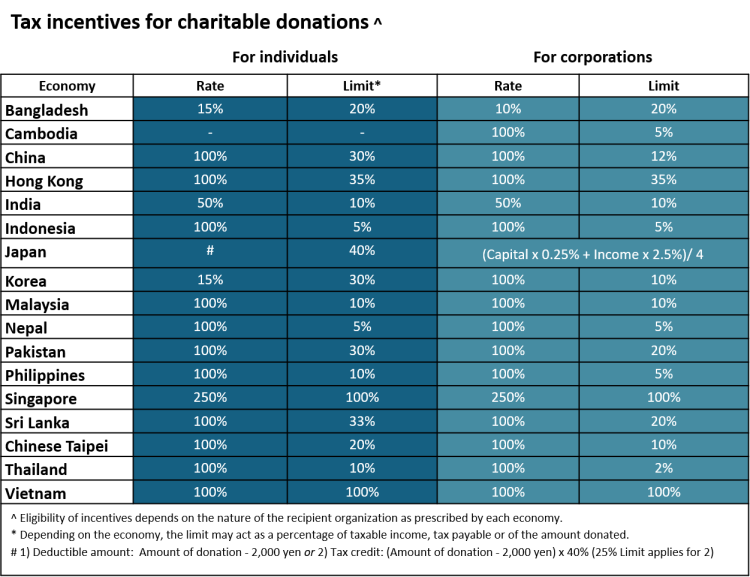

Japan employs a complex formula for calculating the rate of tax incentive for donating to NPOs. Japan is unique in this regard, with all other countries and territories covered in the Doing Good Index using a simple percentage. In most cases, the incentive is more generous, with 12 out of 17 offering a rate of 100% or more (see figure below).

Improving tax incentives for donations – both simplifying the incentive and making it more attractive for donors – could have a positive impact on the fundraising activities of NPOs.

At the same time, alternative funding avenues such as crowdfunding remain underused – just 12% of Japanese NPOs say they are employing crowdfunding, the lowest rate out of all 17 economies in the Index. Indeed, 47% of Japanese NPOs say they intend to raise funds through crowdfunding in the future. This could see a positive boost in both funding and social support for NPOs.

In terms of government regulations, while it is a relatively straightforward process to register as an NPO, 71% of organizations surveyed say that they find social sector laws difficult to understand. Making laws easier to understand, such as through clear communication and informational seminars, for example, will better-equip NPOs to follow regulatory requirements.

Another area where Japan could boost its performance on the Doing Good Index is corporate engagement. Less than half of Japanese NPOs (48%) say they host volunteers from the private sector, lower than the Asian average (63%). Beyond volunteering, NPOs say they would be best supported by corporates providing direct funding, donating products and lending expertise/technical assistance. Companies across Japan should be encouraged to work with NPOs to deliver benefits to communities – after all, it is these communities that represent their customers and service users.

What Japanese NPOs say they need to thrive

When asked what their top three needs are over the next 12 months, NPOs say more funding (60%), upskilling/reskilling of staff (49%) and collaborations with others (46%), closely followed by more staff (44%).

A positive sign for Japan’s NPOs is the next generation. 53% of NPOs say they believe that young people are more interested in working for the social sector compared to their parents. If this is true, it could go some way towards addressing the acute shortages of volunteers and staff within the sector.

And collaboration is also growing, with the number of NPOs saying that they collaborate with others in the social sector increasing from 61% in 2022 to 69% in 2024. These collaborations are essential, with NPOs saying they enter these arrangements to deliver services, advocate for a join cause, improve their capacity, and to conduct research. NPOs are also collaborating with local or state governments and informal citizen-led initiatives to carry out their work. Through these collaborations, the sector can be strengthened and do more.

Of course, many of the changes needed to help the sector to thrive cannot happen overnight, and some fixes are beyond the power of individual NPOs. But if the sector can speak with a united voice on the issues that matter, and commit to ongoing improvement and building of capacity, NPOs in Japan can be empowered to do even more good.

Text by Stephanie Chiang (Research Analyst, Centre for Asian Philanthropy and Society (CAPS))

Stephanie works within CAPS’ research team to deliver evidence-based insights into Asia’s social sectors. Prior to joining CAPS, she has worked across the public, private and social sectors in Australia and Japan, including as a journalist at the Sydney bureau of the The Asahi Shimbun.

Recent Articles

- Changing society from within a 15-minute walk

- How are NPO support centers balancing staff protection and abusive behavior?: Strategies for managing customer harassment

- A view on realignment in U.S. private philanthropy

- Adapting global goals to local action: The SAVE JAPAN Project approach

- JNPOC Launches Grant Project in Partnership with ORIX Life Insurance

- Japanese Translation Available: CAPS Report on Age-Friendly Societies in Asia