The Evolution of Philanthropy: Five approaches shaping contemporary practice InsightsEssays: Civil Society in Japan

Posted on February 18, 2025

The Evolution of Philanthropy: Five approaches shaping contemporary practice

In this series for the Japan NPO Centre (JNPOC), we explore the principles and practices of philanthropy, and consider philanthropy’s transformative potential for Japan’s future. Previously, we looked at the meaning of philanthropy. We examined philanthropy’s origins, and introduced seven criteria to interrogate and map philanthropy: ecosystem, resource, purpose, execution, benefit, context, temporal. This time, we will focus on the history of philanthropy, and examine five different approaches to philanthropy. These are: traditional philanthropy, scientific philanthropy, philanthrocapitalism, justice philanthropy, and relational philanthropy.

Philanthropy’s evolution: Japan and the West

To understand philanthropy, it is important to recognise that philanthropy is not a static concept. It develops over time, incorporates different values, and plays out in various ways across different contexts. To illustrate this, let us look at Japan, where numerous examples associated with elements of philanthropy can be identified. These include the focus on gratitude and reciprocity that are essential to Hōon (報恩, repaying gratitude), On (恩, indebtedness) and Giri (義理, duty and social obligation), the emphasis on corporate and community contributions and responsibilities expressed in Shakai Kōken (社会貢献, social contribution) and Fukushi (福祉, welfare), as well as the ideals of compassion underpinning Jihi (慈悲, compassion), Fureai (ふれあい, interpersonal connection), and Hitozukuri (人づくり, human development and character-building).

All of these ideas have developed over time. This is nicely illustrated by Hōon. Introduced to Japan with Buddhism around 550 CE, Hōon began as a religious principle. Since then, Hōon has developed into a broader moral and social philosophy, absorbing influences from Buddhism, Confucianism, and Shintoism. Alongside, wider socio-economic developments – such as samurai duties, merchant reciprocity, and corporate ethics – have also shaped how Hōon is understood and practiced.

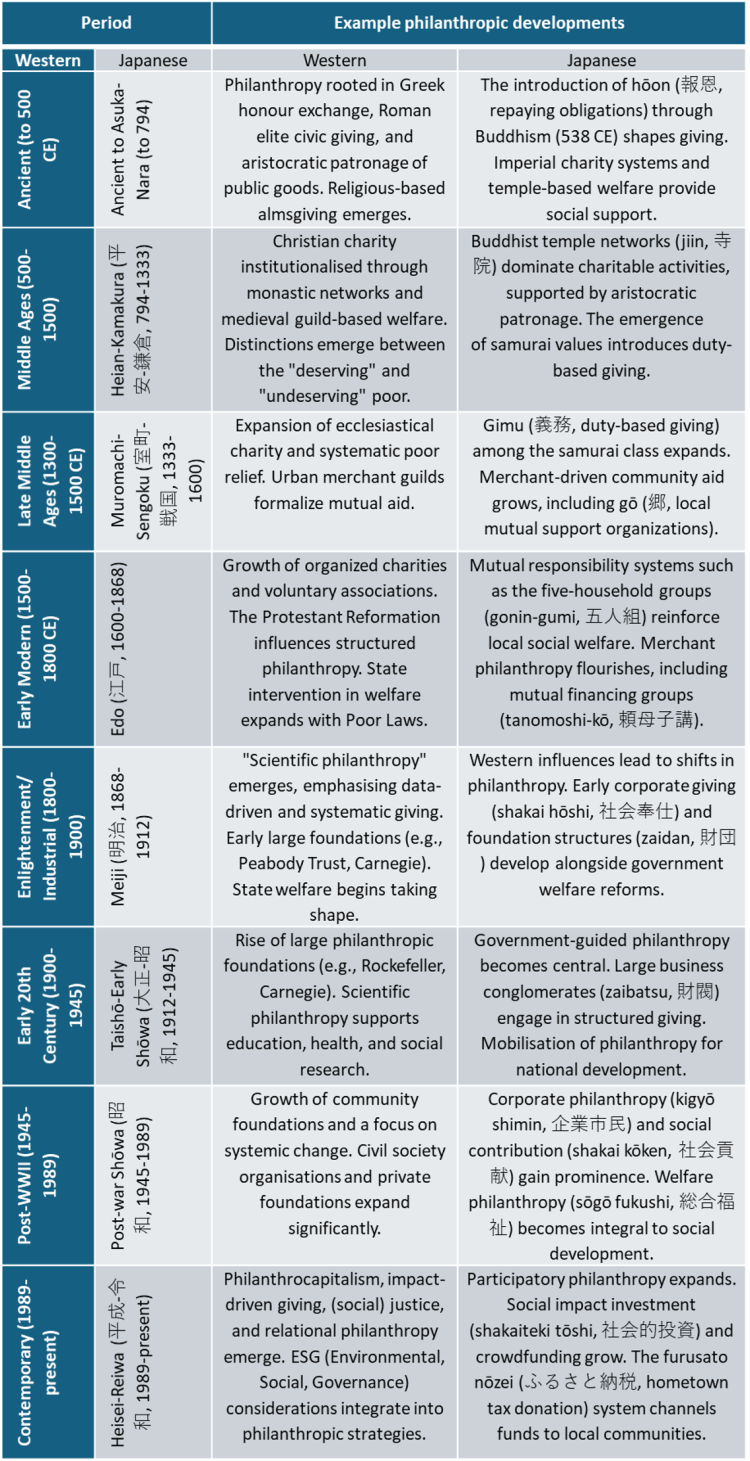

Similarly, Western philanthropy is also a fluid concept. Its motivation and mechanisms, expectations and expressions, have been influenced and shaped by different historical, cultural, and socio-economic contexts. Some of the overarching historical clusters that can be identified in Western philanthropy are outlined in Table 1, and are placed alongside simultaneous developments in Japan. Looking at these clusters, five overarching approaches to Western philanthropy warrant particular attention to understand contemporary philanthropy: traditional philanthropy, scientific philanthropy, philanthrocapitalism, justice philanthropy, and relational philanthropy.

Table 1: Trends Contributing to Philanthropy’s Developments across Western and Japanese contexts

Five approaches to philanthropy: a thought experiment

To explore how each of the five approaches to philanthropy plays out in practice, let us use a thought experiment: imagine you see a hungry person and you would like to help them. How are you going to do this? Traditional philanthropy, scientific philanthropy, philanthrocapitalism, justice philanthropy, and relational philanthropy each offer different answers.

Approach 1: Traditional Philanthropy – For a person in trouble, first give them a fish

Traditional philanthropy focuses on immediate relief. You see a hungry person and give them a fish to eat. This alleviates their hunger for the moment. While the act is compassionate, it does neither addresses the root cause of their need nor support them in the long-term. Once the fish has been eaten, they will be hungry again. The way the interaction plays out, also means that the giver retains power and control, while the recipient remains in a passive role. How can these issues be addressed? This is were scientific philanthropy comes in.

Approach 2: Scientific Philanthropy – Learn to fish, provide fishing rods, and promote sustainable fishing)。

Scientific philanthropy focuses on structured and strategic approaches aimed at long-term empowerment. The idea is rooted in Andrew Carnegie’s The Gospel of Wealth. Born in Scotland in 1835, Carnegie was an industrialist who at the beginning of the 20th Century became one of the richest people in the world. In The Gospel of Wealth, he outlined his thoughts on the responsibilities and uses of wealth. His core argument is that philanthropy should provide the support, and create the conditions, that allow people to help themselves.

Therefore, instead of just giving the hungry person a fish, scientific philanthropy is interested in teaching them how to fish, and providing them with the necessary tools such as a fishing rod. The emphasis thus shifts from the alleviation of hunger to the prevention of hunger.

While skills and tools might be essential, they are not necessarily sufficient if people do not have the information to make the most with these: Where are the best places to fish? Can the fishing be improved through data and technology? How can we scale the solution? These are some of the questions that philanthrocapitalism is interested in.

Approach 3: Philanthrocapitalism – Find the ocean with the most fish, and turn fishing into an investment

Emerging in the 1990s, philanthrocapitalism integrates business principles and practices with philanthropy, and considers social issues as investment opportunities [1]. It emphasises metrics, data-driven decision-making, and market-based solutions. A philanthrocapitalist approach to our thought experiment would explore how fishing could be optimised: what are the best locations for fishing, who would be the best fishers to support, what are the most effective tools for getting the fishing done, and are there any ways to invest in fishing as a business to secure long-term financial sustainability and income.

While this approach enhances effectiveness and efficiency, it also raises concerns about who controls the data and technology, who benefits when philanthropy is treated as an investment, and whether technical solutions are always best for addressing social problems? These challenges lead us to justice philanthropy.

Approach 4: Justice philanthropy – Before you teach me how to fish, clear the way to the river

Justice philanthropy moves beyond efficiency and effectiveness to address equity and systematic barriers [2]. While the previous expressions of philanthropy have focused on empowerment, efficiency, and effectiveness, justice philanthropy asks a deeper question: what do we do if the best, or any, fishing spots are inaccessible? We might have taught someone how to fish. We might have given them a fishing rod. We might even have identified more efficient and effective approaches to do the fishing. But all of this is meaningless if the person we are trying to help cannot reach the river or the sea to actually do the fishing in the first place.

Justice philanthropy is therefore interested in identifying and overcoming such barriers. It wants to ensure that everyone has an appropriate chance to participate and benefit. It is interested in expanding access to resources, encouraging collective decision-making while respecting historical and cultural contexts and working towards long-term harmony by balancing different interests. It asks: How do we ensure that society moves forward together, rather than leaving some behind? How do we ensure that everyone has the opportunity to fish?

While all of these approaches have provided important insights, each of them has overlooked an important question: does the person or the people we are trying to help actually like fish? Have we assumed that fishing is the right solution without first understanding their needs, preferences, or circumstances? This is where relational philanthropy comes into play.

Approach 5: Relational philanthropy – Rather than catching fish, talk to the sea

Unlike the previous approaches, relational philanthropy does not start with an assumption of understanding need, but with dialogue. It recognises that philanthropy can easily impose solutions without consulting those it is trying to help first. Therefore, it shifts the focus from one-way giving to an approach that emphasises mutual exchange and reciprocity [3]. Relational philanthropy recognises that the hungry person and their community hold valuable knowledge that should inform the support provided. Strongly resonating with the ideal of wa (和, harmony), relational philanthropy tries to build trust, mutual respect, and shared decision-making to ensure that solutions are co-created, foster collective well-being and long-term sustainability. The idea is that any philanthropic approach aligns with the needs and values of the individuals and communities it tries to help in order to foster collective well-being and long-term sustainability.

Not one but many: good philanthropy requires all five approaches

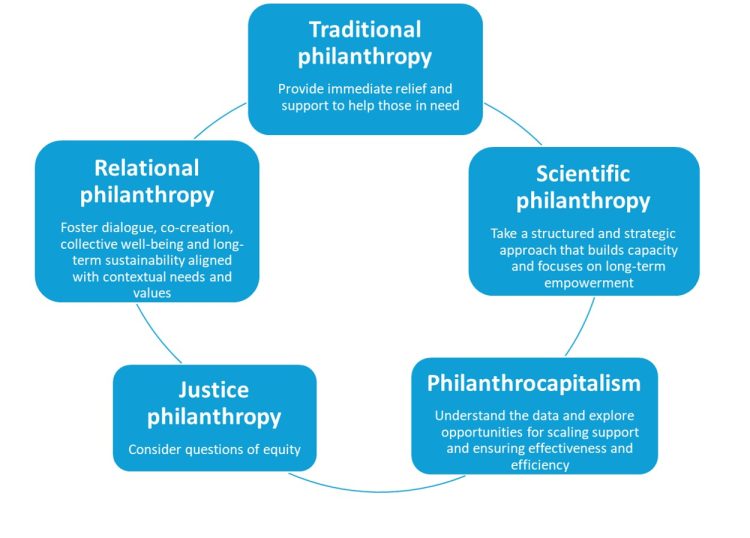

Each of the five approaches to philanthropy offers a valuable lens through which to explore, evaluate, and engage philanthropy. This is outlined in Figure 1. Traditional philanthropy provides immediate relief and support. Scientific philanthropy supports capacity building and empowerment. Philanthrocapitalism enhances efficiency and effectiveness. Justice philanthropy offers equity. Relational philanthropy fosters dialogue, co-creation, and trust. While we have used the example of a hungry person and fish to explore and examine the different emphasis inherent in these approaches, their underlying ideas and ideals apply to all areas of philanthropic engagement whether that be education, healthcare, welfare, or anything else.

Figure 1: Five Complementary Approaches to Philanthropy

Unfortunately, discussions on philanthropy are often dominated by proponents of one approach or another. Such discussions are, however, missing the point: none of these approaches is sufficient on its own. They all have advantages and shortcomings. Instead, the insights they offer need to be considered in tandem. Together, they have the potential to offer us a comprehensive lens through which philanthropy can be examined and practiced. How this can be done, will be the focus of our next blog, where we will bring together the insights from this and the previous blog to offer an integrative framework for exploring and engaging with philanthropy.

References

[1] Haydon, S., Jung, T., & Russell, S. (2021). ‘You’ve Been Framed’: A critical review of academic discourse on philanthrocapitalism. International Journal of Management Reviews, 23(3), 353-375. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12255

[2] Jung, T. (2024). Just Philanthropy? Towards a pragmatic and accountable integrative framework for justice philanthropy. Paper presented at the 16th International Conference of the International Society for Third Sector Research (ISTR), Antwerp, Belgium.

[3] Petzinger, J., & Jung, T. (2024). In reciprocity, we trust: Improving grantmaking through relational philanthropy. Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing, 29(2), e1840. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1840

――――

You can also read the Japanese translation here.

――――

About the author:

Professor Tobias Jung is a leading scholar in the field of philanthropy. He serves as Professor of Management at the University of St Andrews and Director of the Centre for the Study of Philanthropy & Public Good, where he has made significant contributions to understanding philanthropic giving. His research primarily focuses on philanthropic foundations and trusts. Additionally, he is the President of ERNOP (European Research Network on Philanthropy) and a Trustee of Foundation Scotland. In 2023, he was a Visiting Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University.

Recent Articles

- Towards a society where children want to embrace life

- The Evolution of Philanthropy: Five approaches shaping contemporary practice

- 25 years of community understanding and moms’ hard work: The activities of Kinutama Play Village

- Connecting memories: Courage found at the film screening of parents’ legal battle after the Great East Japan Earthquake Tsunami

- An NPO project I came across while reflecting on teacher shortages after leaving my teaching job

- To unlock philanthropy’s potential for Japan, we need to understand its meaning