To unlock philanthropy’s potential for Japan, we need to understand its meaning InsightsEssays: Civil Society in Japan

Posted on October 21, 2024

To unlock philanthropy’s potential for Japan, we need to understand its meaning

As an idea that is almost 2,500 years old, Philanthropy has a long history of addressing social, economic, and political challenges. It has facilitated breakthroughs in education and medical research, supported communities in times of crisis, and enabled advancements in technology and climate solutions. So what can the idea of philanthropy offer Japan? It seems that philanthropy has the potential to act as a catalyst for positive change. It can help with providing the resources, collaborative opportunities, and flexibilities required to drive positive and sustainable impact: from healthcare for an ageing population, to rural revitalisation, and environmental sustainability.

To this end, however, we need to understand the meaning and practices of philanthropy, and consider how these relate to the Japanese context. This is the aim of this blog series. In this first contribution, we will look at the theory of philanthropy: what is the meaning of philanthropy? Next time, we will look at how the practices and principles of philanthropy have developed over time: from scientific philanthropy and philanthrocapitalism, to more recent emphases on relational and social justice philanthropy. Thereafter, we will examine and reflect on how all of this relates to Japan. So, let us begin by exploring the meaning of philanthropy.

The Idea of Philanthropy in Japanese: A Tricky Translation?

Earlier this year, I had the privilege to spend three months as a Visiting Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University, where I worked closely with Professor Toshihiko Ishihara and members of his laboratory to explore and discuss the question of ‘What is philanthropy?’. During this time, I also had the opportunity to present some of these reflections to members of the Japan NPO Research Association (JANPORA). Based on these, and other, conversations, it appears that the meaning of philanthropy presents a bit of a challenge in Japanese. As far as I can see, the term philanthropy was introduced to Japan around the 1980s and 1990s. Sometimes, it is transcribed in katakana as ‘フィランソロピー firansoropi’. At other times, philanthropy is translated as 慈善 jizen, charity, or as 博愛 hakuai, benevolence. Very often, it seems to have become strongly associated with the idea of ‘corporate philanthropy’, rather than with philanthropy in its wider, more encompassing, sense. As such, the term comes across as lacking clarity; it appears that it is frequently seen and used in an ambiguous matter. This ambivalence of the term’s meaning is not unique to Japanese; it is a wider issue in the philanthropy field. A lack of shared understanding of philanthropy’s meaning does, however, present a number of challenges. It limits meaningful knowledge-exchange on philanthropy, and makes it difficult to

- share and compare insights and lessons on philanthropy,

- inform and guide relevant practices and policies related to philanthropy,

- promote public understanding and engagement with philanthropy, and

- align efforts to identify philanthropy’s impacts and outcomes.

In short, a lack of shared understanding undermines the extent to which philanthropy’s potential can be unlocked and used.

The Challenge of Defining Philanthropy

The origins of the term philanthropy go back to Ancient Greece. The term first appears around 430BC in the Greek tragedy Prometheus Bound to describe the moment when the Greek Titan Prometheus, out of his philanthropos tropos, his human loving nature, presented humans with two complementary gifts: fire and blind hope. Fire was an analogy for knowledge and skill; blind hope was meant to symbolise optimism and the willingness to innovate. On that basis, philanthropy is often considered as meaning ‘the love of humanity’. How this plays out in practice, however, has been difficult to define.

Over the years, definitions have tried at least five different ways to address this. Firstly, authors have emphasised the emotional or motivational aspects of philanthropy. A second approach has been to unpack the actions or behaviours that philanthropy might entail, while a third one has focused on the resources that can be used or transferred in philanthropy. Fourthly, authors have tried to highlight the broader societal effects or goals of philanthropy, while a final approach has been to look at the institutional and structural aspects of philanthropy. While each of these offers important insights on how we can understand philanthropy, they only provide a partial picture: they do not help to differentiate philanthropy from related concepts, such as charity, social investment, or corporate social responsibility. How then can we better understand philanthropy?

Seven Criteria of Philanthropy

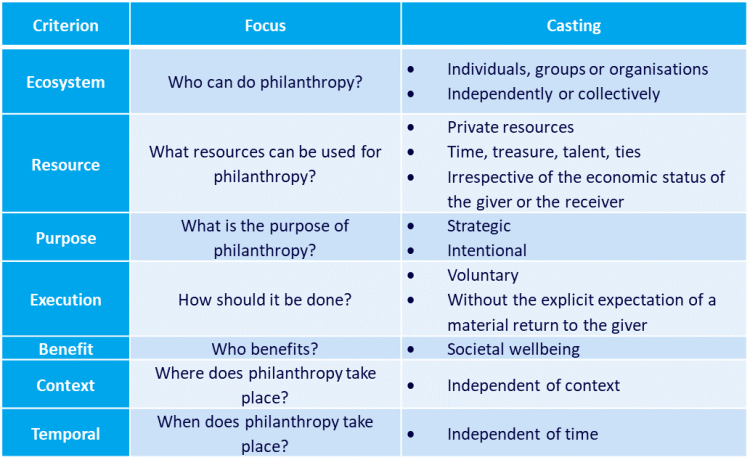

To fully understand and utilise philanthropy, it is important to identify its core characteristics. Based on my research on philanthropy over the last 15 years, seven criteria seem to encapsulate the core of what constitutes philanthropy. These are outline in the table. Together, they provide the basis for an integrative definition and theory of philanthropy.

- The Ecosystem Criterion: Who can do philanthropy? Philanthropy is often associated with the rich, the wealthy, and large corporations. This is a popular misconception. The philanthropic ecosystem is far more encompassing. It is not limited to any special class, cohort, or category. Philanthropy is open to everyone. It is important to recognise that it covers all levels and includes individuals, groups, and organisations that can act either independently, on their own, or collectively and collaboratively with others.

- The Resource Criterion: What resources can be used for philanthropy? Philanthropy is often thought of as only relating to financial donations, the giving of money to causes or institutions. This is view is too narrow. In the philanthropy field it is recognised that any form of resources can be useful. This is covered by, and referred to, as the four ‘Ts’ of philanthropy:

- Time: volunteering or dedicating time,

- Treasure: providing financial or material assets,

- Talent: sharing skills or expertise, and

- Ties: the social networks and connections.

This broader understanding of philanthropic resources not only democratises philanthropy, but also highlights that everyone, independent of their economic status, has something to contribute. Nobody is too poor to act philanthropically.

- The Purpose Criterion: What is the purpose of philanthropy? Unlike charitable giving, which is focused on alleviating immediate need, philanthropy is geared towards addressing the root causes of underlying problems. As such, it needs to be strategic and intentional. Rather than focusing on one-off acts of kindness, it has to take a long-term perspective for sustainable systemic solutions.

- The Execution Criterion: How should philanthropy be done? A core characteristic of philanthropy is that it is voluntary in nature. It is driven by choice rather than compulsion. This distinguishes philanthropy from taxation and other forms of mandatory or obligatory giving.

- The Benefit Criterion: Who benefits from philanthropy? Philanthropy should not come with an explicit expectation of a material return to the giver: it should be done without seeking financial gain or material benefits. This differentiates philanthropy from areas such as corporate social responsibility and cause related marketing, where there may be clear expectations of financial returns. Instead, philanthropy is about enhancing wider communal or societal good, whether through education, healthcare, poverty alleviation, or environmental sustainability. This collective, communal, orientation distinguishes philanthropy from self-serving acts of generosity that are primarily motivated by personal gain.

- The Context Criterion: Where does philanthropy take place? Philanthropy is context dependent but must not be limited by specific settings. So, while philanthropy occurs within different geographical, cultural, and political contexts – philanthropy in Japan, might look different from philanthropy in Germany or in Scotland – they are all valid forms and expressions of similar core practices as per the preceding criteria.

- The Temporal Criterion: When does philanthropy take place? Philanthropy is neither confined to a particular era or period, nor is it bound by time. While specific philanthropic actions happen at particular moments, the underlying principles and practices transcend these. This criterion is essential for understanding philanthropy as an ongoing effort that adapts to contemporary contexts and challenges.

Based on these criteria and taking their defining characteristics into account, philanthropy can be understood as the following:

Philanthropy, is the voluntary provision, and strategic and intentional use, of private resources – time, treasure, talent, ties – irrespective of the economic status of the giver or the receive, by individuals, groups, or organisations, acting either independently or collectively, and without the expectation of a material return to the giver, aimed at enhancing societal well-being, independently of contexts or times.

This definition clearly demarcates philanthropy from other, related, concepts such as charity or benevolence. It highlights the complexities of philanthropy while remaining flexible enough to accommodate the diversity of contemporary philanthropic practices. It also shows that philanthropy is not confined to certain categories or class of citizens or corporations, but that philanthropy is an activity that anyone can and should participate in. What does this definition offer to those interested in the non-profit field?

Practical implications

For those who are stakeholders or interested in the non-profit field – whether through working in the area, by supporting it, or making relevant policies — the outlined definition of philanthropy and its underpinning criteria offer a number of points for reflection and action. First of all, it indicates that if we are interested in encouraging philanthropy we need to provide opportunities to engage in philanthropy for all parts of society, whether that be through their treasures, time, talents, or ties. Secondly, it reminds us that philanthropy needs to be structured and supported in ways that allow for sustainable, lasting, long-term, impact, rather than just harnessing philanthropy for immediate or temporary relief. As part of this, any framework geared towards encouraging philanthropy must not feel obligatory. It is critical to create incentives that support voluntary contributions focused on broader collective and societal impact while ensuring that these contributions do not become perceived as an alternative to, or substitute for, government responsibilities. Finally, we need to remember that an approach to philanthropy needs to be flexibly and adaptable. We need to recognise the diversity of contexts within which philanthropy can occur, and ensure that practices and policies are inclusive enough to align with different local conditions.

I look forward to exploring how philanthropy has played out in practice over the years, and to highlight some of the contemporary practices and considerations, such as philanthrocapitalism and relational philanthropy, in the next iteration of this blog series. Lastly, I am very grateful to the Japan NPO Center for the opportunity to provide these reflections on the meaning of philanthropy.

――――

You can also read the Japanese translation here.

――――

About the author:

Professor Tobias Jung is a leading scholar in the field of philanthropy. He serves as Professor of Management at the University of St Andrews and Director of the Centre for the Study of Philanthropy & Public Good, where he has made significant contributions to understanding philanthropic giving. His research primarily focuses on philanthropic foundations and trusts. Additionally, he is the President of ERNOP (European Research Network on Philanthropy) and a Trustee of Foundation Scotland. In 2023, he was a Visiting Professor at Kwansei Gakuin University.

Recent Articles

- Towards a society where children want to embrace life

- The Evolution of Philanthropy: Five approaches shaping contemporary practice

- 25 years of community understanding and moms’ hard work: The activities of Kinutama Play Village

- Connecting memories: Courage found at the film screening of parents’ legal battle after the Great East Japan Earthquake Tsunami

- An NPO project I came across while reflecting on teacher shortages after leaving my teaching job

- To unlock philanthropy’s potential for Japan, we need to understand its meaning