“We cannot survive like this!” Toward a better future protecting tomorrow for the foreigners without status of residence InsightsEssays: Civil Society in Japan

Posted on May 31, 2023

Japan NPO Center (JNPOC) has a news & commentary site called NPO CROSS that discusses the role of NPOs/NGOs and civil society as well as social issues in Japan and abroad. We post articles contributed by various stakeholders, including NPOs, foundations, corporations, and volunteer writers.

For this JNPOC’s English site, we select some translated articles from NPO CROSS to introduce to our English-speaking readers.

“We cannot survive like this!” Toward a better future protecting tomorrow for the foreigners without status of residence

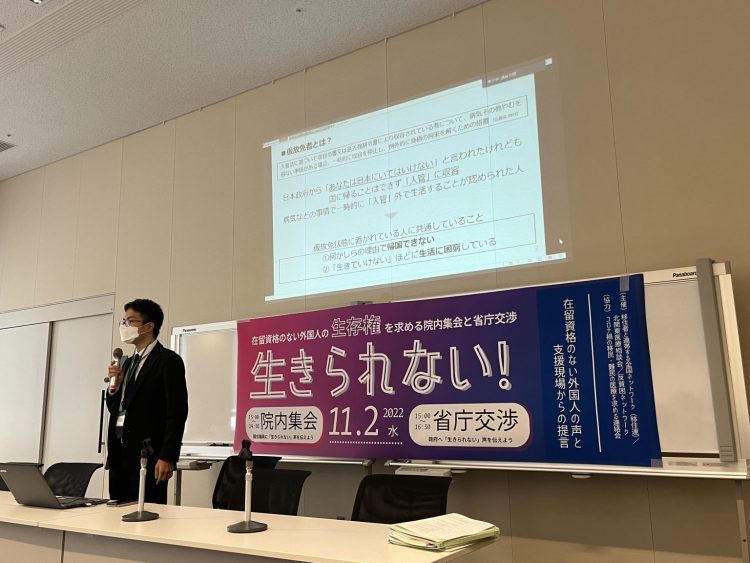

November 2, 2022. At the rally held in a conference room at the Second Members’ Office Building of the House of Representatives, people raised their voices and said, “We cannot survive like this!” These were the voices of foreigners without legal residential status and of the staff of organizations supporting them.

Status of residence, in a nutshell, is a status that allows foreigners to stay “legally” in Japan. It is issued under the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act, or the so-called Immigration Control Act.

What happens to those who do not have a status of residence?

In the conference room, participants are listening to the voices of the foreigners without status of residence and the organizations that support them as they discuss bleak conditions. [Photo courtesy of the Anti-Poverty Network]

In the conference room, participants are listening to the voices of the foreigners without status of residence and the organizations that support them as they discuss bleak conditions. [Photo courtesy of the Anti-Poverty Network]

Where Foreigners Without Status of Residence End Up

Foreigners without a status of residence are subject to violation investigations conducted by the Immigration Services Agency of Japan (ISA). If a detention order is issued after this investigation, the said foreigner will be detained in an immigration detention facility. In such cases, the detention period is limited, with a maximum of 60 days. If ISA determines deportation as the final result after detention, this person will be in the process of deportation or repatriation.

However, there are cases in which the person “refuses” to be deported. The main reasons are that returning to their home country would put the person’s life in danger or that they would be separated from their children1 who are educated in Japan. Foreigners who fear for their lives if they return to their home country can obtain refugee status if they are officially recognized as refugees, but there are many people whose asylum applications are not recognized. This is because Japan’s asylum recognition rate is lower than 1%. This figure is the lowest among the G7 nations. In result, many asylum applicants are simply unable to acquire any legal status of residence in Japan.

Prolonged detention of those without a status of residence becomes a problem. Once deportation order is issued, there is no upper limit to the period of detention for foreigners who refuse to be deported. The term of detention is legally set as “until deportation become possible,” which makes it almost indefinite.

There has been much criticism regarding the human rights of foreigners in detention. In March 2021, a Sri Lankan woman was found dead in the immigration facility in Nagoya. In November 2022, an Italian man was also found dead in the immigration facility in Tokyo. Such deaths had occurred in the past as well, and there are some questioned raised about the immigration system.

Provisional Release System as Exemption of Detention

However, it is not the case that all those who are issued a detention order are detained inside immigration facilities.

In Japan, there is a system called provisional release (KARIHOUMEN), under which some people are allowed to live temporarily outside the immigration facility even if they have been given detention orders. According to the ISA website, there were 4,174 people on provisional release as of the end of December 2021.

The circumstances of those who are granted provisional release vary, including those who need to receive regular medical care for health reasons and those who are allowed to live with their families. Some students who were born in Japan to parents without status of residence are living on provisional release.

The people who proclaimed, “We cannot live like this!” on this day at the rally are foreigners who cannot obtain a status of residence even though they are willing to take the status. This rally that took place in a conference room of the Diet Members’ Building was held by the organizations supporting these foreigners. It was followed by negotiations with officials from the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. The venue was packed. I witnessed this via live streaming on YouTube.

The overall theme of the day was “Rally and Ministry Negotiations for the Right to Live for Foreigners without Status of Residence: We Cannot Survive Like This! – Current Conditions of Foreigners without Status of Residence and Proposals from Supporters on the Ground” (in Japanese).

The event was organized by the following three organizations:

- Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan (SMJ)

- Amigos (also known as North Kanto Medical Consultation Association)

- The Anti-Poverty Network

They made proposals to the government on the state of public assistance for foreigners without status of residence and on other policy issues.

So what kind of problems do provisional releasees (KARIHOUMENSHA) face?

Reality Awaiting Provisional Releasees (KARIHOUMENSHA)

Mr. Yuma Osawa of Amigos argues that “in order to survive, provisional releasees should be given work permissions.”

The current immigration law does not allow for provisional releasees to work. Since provisional releasees cannot work, they have no source of income. This ends up in the releasees being “so impoverished that they cannot survive,” Mr. Osawa says. On the other hand, if they violate the law and do any kind of job for pay, then their provisional release is revoked, and they are detained at the ISA detention facility.

Being unable to work means they cannot pay their rent and medical bills, let alone afford the food they eat day to day. To get out of this dilemma, Mr. Osawa insisted that, first and foremost, “releasees should be given permission to work.”

There is something that is not allowed for the provisional releasees—health insurance coverage. As a result, medical treatment at medical facilities become inevitably expensive.

“ISA has no idea about how someone’s health issues can be supported. The only opinion they have is, ‘Gaijin (foreigners) should leave Japan,’” pleads a man from South America who is living in Japan as a provisional releasee. He has tinnitus as a condition resulting from the persecution and torture that he had suffered in his home country. When he received treatment at a medical facility here in Japan, he was charged a total of 2.5 million yen for surgery and hearing aids.

He is not the only provisional releasee suffering from illnesses. According to Mr. Masataka Nagasawa of Amigos, there were eight provisional releasees requiring surgery between April and December of 2022.

The aforementioned man later underwent surgery at another medical facility with the support of Amigos. The treatment cost was 820,000 yen. Mr. Nagasawa closed his statement, saying, “We will continue to assist those who need our support. We appreciate your cooperation and support.”

On this day, three support organizations explained the current conditions of provisional releasees.

[Photo courtesy of the Anti-Poverty Network]

Appeals of Civil Society Organizations Supporting Foreigners

“They also have the right to get proper health care, housing, and employment,” says Mr. Bunjiro Hara of the Anti-Poverty Network for those without legal status of residence.

“It does not matter which nationality a person has or what their country of origin is. We are all the same as we all have to live as human beings.” But the reality is that their livelihood depends solely on non-governmental support.

Actually, the amount of support has been increasing each year. According to a report by Ms. Sachi Takaya of Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan, during the two and a half years from April 2020 to September 2022, the support provided by the three organizations amounted to 173.24 million yen. However, this amount does not even cover what it takes to secure people’s minimum livelihood, as “the status quo of support is that it only amounts to a tiny drop in the bucket for each individual provisional releasee.” In other words, they are not able to continuously pay the releasees’ rent, nor are they able to give enough money to cover the fees at medical facilities. It is unreasonable to think that it can continue like this.

As Ms. Takaya called for either “granting a status of residence and opening a path to work for those who can,” or “guaranteeing the right to live regardless of whether or not someone has a status of residence,” the rally was concluded.

“If We Don’t Do Anything, Many Foreigners Would Die.”

The rally was followed by negotiations with the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare officials.

Mr. Daisaku Seto of the Anti-Poverty Network addressed the current situation: “If civil society organizations do not step in to help, many foreigners will die.” In fact, Mr. Seto noted that civil society organizations are slowly approaching their limit in the support they can give towards maintaining the livelihoods of provisional releasees. Especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, their activities have been restricted, and it has also become financially difficult for civil society and religious organizations to support the releasee.

“Please come and see with your own eyes what’s really happening on the ground,” a voice in the audience pleaded. After an hour and a half of ministry negotiations failing to reach any agreement, Mr. Seto added, “We would like to try again before the end of the year.”

Continuing to Bring Voices from the Front Lines Will Lead to a Better Future

Before entering into negotiations with the ministries, an affiliate group supporting the initiative called Medical Services for All Migrants and Refugees Under COVID-19 Pandemic collected petitions and submitted them to the government. The petition called for a revision of the system so that immigrants and refugees would not be charged high medical fees. The total number of signatures reached 46,977.

I firmly believe that when we continue to deliver the voices of the people on the ground to the right places, we can brighten the tomorrow for foreigners without status of residence as well as bring a better future.

[1] In 2012, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) issued a document that mentions that children without status of residence should be allowed in effect to attend school.

Reference links

- Immigration Services Agency of Japan, Ministry of Justice

- “Rally and Ministry Negotiations for the Right to Live for Foreigners without Status of Residence: We Cannot Survive Like This! – Current Conditions of Foreigners without Status of Residence and Proposals from Supporters on the Ground”

- Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan (SMJ)

- Amigos (also known as North Kanto Medical Consultation Association)

- Anti-Poverty Network.

- Medical Services for All Migrants and Refugees Under COVID-19 Pandemic

Original text by Erika Schneider (JNPOC’s volunteer writer) originally posted on December 14, 2022; translated by JNPOC. Ms. Schneider virtually attended the “Rally and Ministry Negotiations for the Right to Live for Foreigners without Status of Residence: We Cannot Survive Like This! – Current Conditions of Foreigners without Status of Residence and Proposals from Supporters on the Ground” organized by the Solidarity Network with Migrant Japan’s (SMJ).

Recent Articles

- The Evolution of Philanthropy: Five approaches shaping contemporary practice

- 25 years of community understanding and moms’ hard work: The activities of Kinutama Play Village

- Connecting memories: Courage found at the film screening of parents’ legal battle after the Great East Japan Earthquake Tsunami

- An NPO project I came across while reflecting on teacher shortages after leaving my teaching job

- To unlock philanthropy’s potential for Japan, we need to understand its meaning

- Cultivating a healthier agricultural and societal foundation: Passing on the knowledge and practices of environmental regeneration to future generations