A Tough Country for Foreigners to Live? What Japanese society has not been able to do and what we can start doing now InsightsEssays: Civil Society in JapanVoices from JNPOCOther Topics

Posted on December 16, 2020

In 2018, Japan NPO Center (JNPOC) started a news & commentary site called “NPO CROSS” to discuss the role of NPOs/NGOs and civil society as well as social issues in Japan and abroad. We post articles contributed by various stakeholders, including NPOs, foundations, corporations, and volunteer writers.

For this JNPOC’s English site, we select some translated articles from NPO CROSS to introduce to our English-speaking readers.

A Tough Country for Foreigners to Live?

What Japanese society has not been able to do and what we can start doing now

The article was covered and written by Ryoko Sato, a volunteer writer of the Information Dissemination Volunteer Project by Japan NPO Center.

Interviewee: Mr. Isao Nagasawa, Executive Director, Kanagawa Housing Support Center for Foreigners

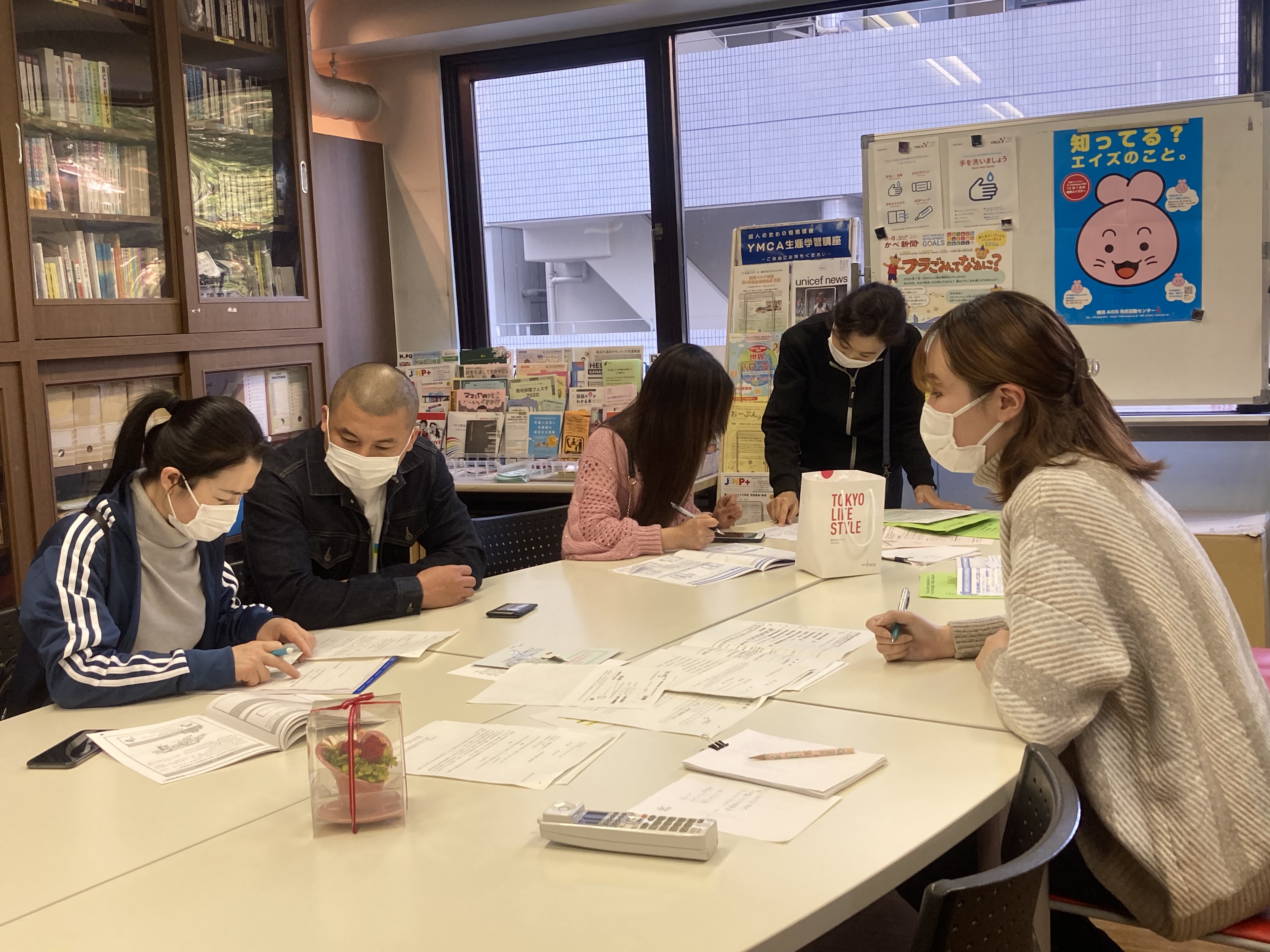

Foreign residents consulting with SumaSen staff. © Kanagawa Housing Support Center for Foreigners

With the amended Immigration Control Act (Act for Partial Amendment of the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act of 2014), which established a new status of residence, coming into effect in April 2019, the number of foreign nationals coming to Japan is expected to increase. However, there are current foreign residents in Japan who do not enjoy the bare minimum of what a person needs to live, as exemplified in the phrase, “Able to feel safe, able to eat, and able to sleep.” This is a phrase Mr. Isao Nagasawa has repeated several times. Mr. Nagasawa serves as Executive Director of the Kanagawa Housing Support Center for Foreigners (Kanagawa Gaikokujin Sumai Sapoto Senta, hereafter abbreviated as SumaSen), which has been providing housing and livelihood support for around 20 years. Describing the circumstances of the people who come to SumaSen, he said, “They are human beings who are not treated as human beings.”

From housing support to livelihood support

In the 1990s, one of the major problems faced by foreigners living in Japan was finding a place to live. They were sometimes shunned by landlords who were afraid of trouble because foreign residents often could not find guarantors, and there were also differences in language and customs. In order to tackle these housing issues, a proposal from the Kanagawa Prefecture Council of Foreign Residents became the impetus to launch SumaSen in 2001 with cooperation among ethnic organizations, regional international associations (which are extra-departmental organizations of local municipal governments), municipal governments, and NPOs.

Over the years, SumaSen has helped create an environment where foreign residents could rent housing more easily. This was done with cooperation from real estate agencies who could introduce properties to foreigners and through SumaSen responding to troubles foreign residents, landlords, and real estate agencies faced. However, the number of cases SumaSen receives has only increased. “More and more people are coming to us on matters concerning debt, labor conditions, pensions, disabilities, ageing, family problems, domestic violence, financial hardships, and other issues that loom over their heads before they can even look for a home,” says Mr. Nagasawa.

SumaSen received a phone call from a man from Peru who had only been in Japan for about two days. “I came to Japan with very little money and I’m staying at a manga café* in Kawasaki City now. I need your help because I want to rent housing,” he said. Having obtained permanent resident status about 10 years ago, he could come into Japan quite easily. When the staff told him to come to SumaSen, he said he could not because he did not have the money for transportation. The staff ended up picking him up at the manga café, and from there, they took him to City Hall to consult with the Welfare Department. First and foremost, people need a safe environment. So, SumaSen followed the procedures and the man was placed temporarily in a facility run by an organization supporting the homeless. Fortunately, he was able to find a job right away, so the plan was that he would work first until he had some money to spare, and then this organization that supports the homeless can help him find a place to live at that point. (*A manga café offers comic books to read and often also internet access to its users for an hourly or daily rate, including overnight stays. Just like internet cafes, it often serves as a refuge for the housing insecure.)

“The bare minimum for a person to sustain their life would be to eat and to sleep. If we can’t even secure these two things, we can’t move on to the next step,” says Mr. Nagasawa. In the last few years, there has been an increase in the number of preliminary steps needed to help clients reach the point where they can be referred to a real estate agent. So now while half of the work SumaSen does is housing support, the other half is in general livelihood support.

Language problems

Why is there such an increase in the need for livelihood support?

“Language is a big problem for foreigners living in Japan. But the Japanese government is opening the doors for more people to come live in Japan without doing its part in making sure people can learn Japanese. In fact, the government has not established any systemic support for language learning,” says Mr. Nagasawa, who has responded to numerous foreigners in need over the years.

In fact, there are many people who ask for help from SumaSen because of their lack of Japanese language skills. A Chinese man who had lived in Japan for more than 10 years and worked in a Chinese restaurant could not read a Japanese manual when he moved to a public housing complex, so he asked for help from SumaSen. He needed instructions on everything from how to start using the faucet in the bathroom to how to turn on the gas in his unit. In Japan, there is no public support for learning the Japanese language or being familiarized with Japanese life and culture. There are many foreign residents who cannot read or write Japanese even after living here for many years.

SumaSen Staff members assisting non-Japanese residents to fill out public housing applications. © Kanagawa Housing Support Center for Foreigners

In some countries that accept immigrants, there are publicly provided opportunities for immigrants to acquire language skills and knowledge about life and culture, all of which they need to survive in the country. In Germany, for example, there are social integration programs that are government led and consist of a German language course and an orientation course that cover German history, culture, and laws. The aim of the German language course is to enable students to reach adequate proficiency in German so that they would not be in trouble in their everyday lives.

A dysfunctional system

In Kanagawa, there are systems and services put in place to support foreign residents. However, these do not necessarily function well from the perspective of those who need to use them. For instance, public schools utilize a system to support parents who are unable to read Japanese, because schools typically hand out announcements and other information for parents on paper. Under the current system put in place, an individual teacher at the school must first put in a request with a local international association affiliated with the municipal government to have an interpreter dispatched to the school. The teacher and the parent must set up a meeting at the school, and the interpreter will accompany them there to explain the contents of the handouts.

This service is free for the foreign parents and guardians, but it is only available during regular working hours on weekdays, so it is almost impossible for working parents to use. Parents would inevitably bring a large number of handouts to SumaSen to know what the school intended to communicate with them, and the actual explanation of the contents may only take about half an hour.

Even though there is a system for support, the question remains as to whether the services offered actually match the needs of the intended users.

One-stop support service

Mr. Nagasawa notes, “We at SumaSen would like to provide one-stop support for our clients as much as possible. Our motto is to hold on to a case until all the issues are fully resolved and when the client can move on to the next step.” And because of this motto, SumaSen’s scope of support extends to various livelihood issues.

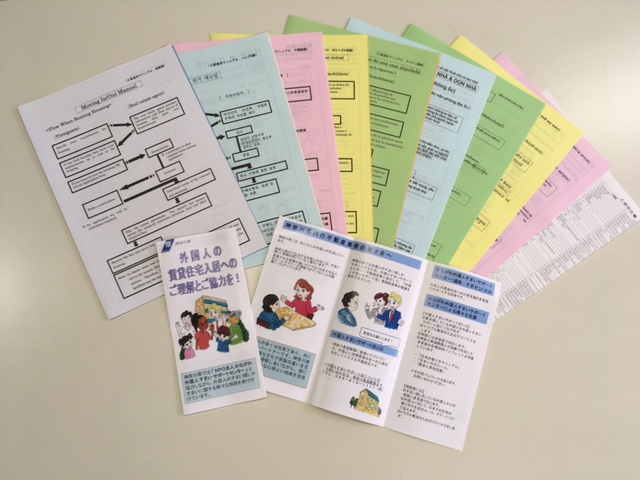

If you put yourself in the foreign resident’s shoes, it would be ideal for the municipal government to provide this one-stop support. So, about ten years ago, in order to solve the language problems that lie between foreign residents and the municipal governments, SumaSen created the Municipal Government Multilingual Manual in five languages. To make it easier for government workers to understand what the foreign residents are trying to find out, the manual categorizes typical everyday issues such as education or work, and under each category you can find a set of common questions and answers.

The Municipal Government Multilingual Manual in five languages created by SumaSen © Kanagawa Housing Support Center for Foreigners

Suggestions for joining neighborhood associations

——————–

March 26, 2020

Original text by Ryoko Sato (JNPOC’s volunteer writer); translated by JNPOC

Recent Articles

- Towards a society where children want to embrace life

- The Evolution of Philanthropy: Five approaches shaping contemporary practice

- 25 years of community understanding and moms’ hard work: The activities of Kinutama Play Village

- Connecting memories: Courage found at the film screening of parents’ legal battle after the Great East Japan Earthquake Tsunami

- An NPO project I came across while reflecting on teacher shortages after leaving my teaching job

- To unlock philanthropy’s potential for Japan, we need to understand its meaning