“Because you’re a girl/boy” closes off possibilities: Dismantling gender stereotypes InsightsEssays: Civil Society in JapanVoices from JNPOCOther Topics

Posted on December 21, 2022

In 2018, Japan NPO Center (JNPOC) started a news & commentary site called NPO CROSS to discuss the role of NPOs/NGOs and civil society as well as social issues in Japan and abroad. We post articles contributed by various stakeholders, including NPOs, foundations, corporations, and volunteer writers.

For this JNPOC’s English site, we select some translated articles from NPO CROSS to introduce to our English-speaking readers.

“Because you’re a girl/boy” closes off possibilities:

Dismantling gender stereotypes

Although I thought we have gradually become more aware of gender equality in Japan over the past few decades, the World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Index says otherwise. The index shows the disparity between men and women in each country, and the most recent report has revealed that Japan is still facing a number of challenges with the gender gap, having ranked 120th out of 156 countries. Plan International Japan (PIJ) maintains that the key to improving this situation is to dismantle gender stereotypes.

Gender stereotypes are gender-related fixations that permeate our society. Thinking that babies wear pink if they are girls and blue if they are boys is an example of a gender-related stereotype, a gender stereotype.

According to PIJ’s report titled “Stepping out of the gender box: Gender stereotype survey of Japanese high school students” (in Japanese), young people have internalized gender stereotypes as part of their values in their early teens and they solidify around the age of 15 to 16. To protect children and youth from gender-based limitations and discrimination, PIJ surveyed 2,000 Japanese high school students on their gender stereotypes and values as well as the influences and experiences of these stereotypes. I participated in their online report release event called “The Reality of Gender Stereotypes Among Japanese High School Students” held on May 12, 2022.

Gender Images and Stereotypes

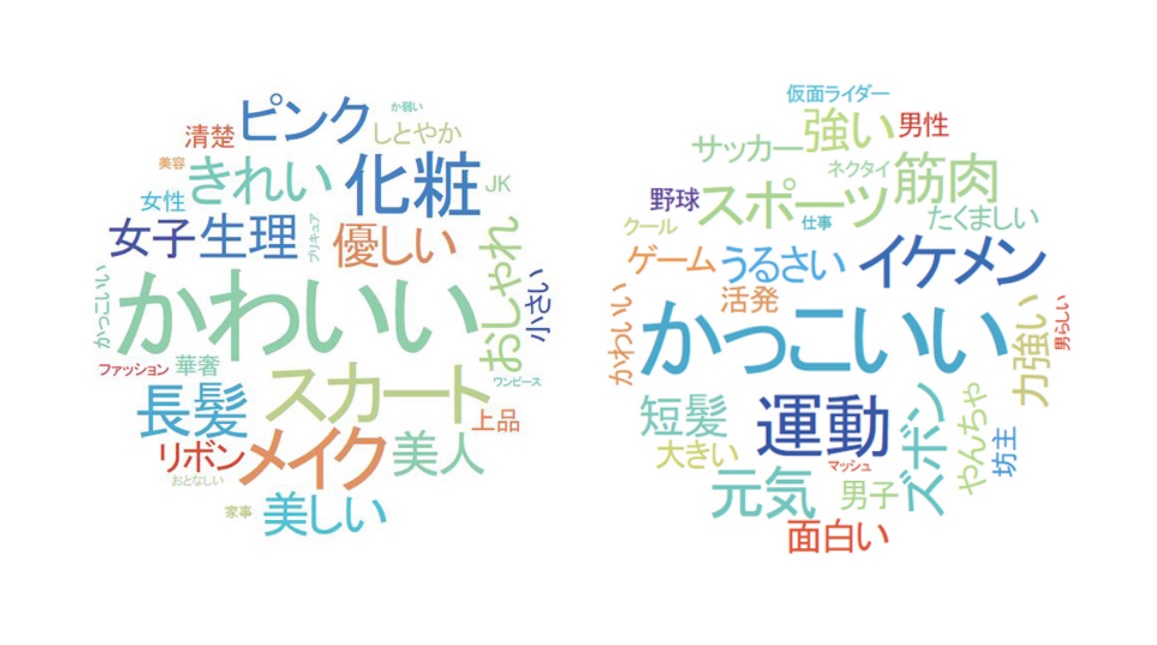

The PIJ survey consisted of 15 questions in 4 sections. To understand what gender images these high school students have, the first section contains a question that asks them to name three words that come to mind when they think of “girls” and “boys.”

Respondents were more likely to list words related to physical appearances, such as “kawaii (cute)” and “utsukushii (beautiful),” for girls than for boys, and although few, words related to the family were also listed for girls. On the other hand, while the most common words associated with boys were “kakkoii (cool),” there were many that represented strength and being active, such as “muscle” and “exercise.” Finally, words that came up only for boys included those associated with work, such as the Japanese verb for “work,” “salaryman (male white-collar worker),” and “breadwinner.”

I was struck by the fact that we saw words about work only in association with boys. At the same time, I found it unsurprising that a lot of appearance-related words came up for girls and strength-related words for boys, as I expected that to be the case. My lack of surprise unfortunately means that I have espoused gender stereotypes myself. However, we must keep in mind that there are differences in how strongly someone believes in gender stereotypes.

In the survey, PIJ categorized the degree to which the 2,000 respondents espoused gender stereotypes as strong, mild, or weak.

To measure the strengths of gender stereotypical beliefs, respondents were shown 13 statements that contained gender stereotypical thinking and asked if they “agree,” “somewhat agree,” “somewhat disagree,” or “disagree” with the statement. They got 4 points for “agree,” 3 for “somewhat agree,” 2 for “somewhat disagree,” and 1 point for “disagree,” thus those who chose “agree” more often ended up with higher scores, which also indicates that they have strong gender stereotypes.

Let us look at the correlation between self-identified gender categories and how strongly the respondents espoused gender stereotypes.

Among those who identified their gender as “other,” 90% were found to have weak gender stereotypes. This was the highest percentage among all gender categories, followed by 35.4% of those identifying as “female” having weak gender stereotypes. In contrast, among those with strong gender stereotypes, “males” had the largest percentage, meaning boys most strongly espoused gender stereotypes.

Now, some readers may be unfamiliar with “other” as a gender identity. In this survey, respondents were asked to indicate their self-identified gender, which may or may not be different from their assigned sex at birth. Respondents who answered “other” for their gender identity may be neither female nor male, or they may feel both female and male, or they may be unsure or undecided.

Experiences of seeing, hearing, or being told gender stereotypical expressions and remarks

The second section asked whether the respondents had seen, heard, or experienced gender stereotypical expressions or remarks.

Overall, 27.2% of respondents answered “yes” to this question. 68.4% of the respondents who identified as “other” said yes, which was a prominently large figure. In addition, more girls answered “yes” than boys.

In response to the question about what types of stereotypical remarks to which the respondents have been exposed, the survey results revealed that girls had been told to “do chores” or to “be modest” just because they are girls, whereas boys were often told they “should not cry” or “should be good at sports.”

As for where these gender stereotypical expressions or remarks were seen and heard, the school was found the most common place at 70%, with the home comes second.

During the panel discussion during the report release event, someone commented on gender stereotyping in schools that “teachers themselves have been raised under the influence of gender stereotyping, and this influence might be reproduced in the educational setting,” and it left a deep impression on me.

Impact of gender stereotypes

The third section had a question that asked whether the respondent felt stereotypical remarks limited their possibilities. 70% of the respondents answered “agree” or “somewhat agree.” This was particularly high among those with the “other” gender identity, and girls were more likely to agree or somewhat agree than boys. Some have heard “boys are better suited for the sciences” or even said, “I tend to give up what I really want to do because I worry about how I appear to others.” The “other” gender-identified respondents were particularly likely to feel stressed by stereotypical comments from those around them.

The fact that as many as 70% of high school students felt that their possibilities are limited by the comments of those around them may be due in part to the unique collectivist Japanese culture where people are concerned about other people’s opinions of them. I feel that changing this part of the culture will help resolve not only these limitations posed by gender stereotypes but other everyday difficulties in life as well.

Gender stereotypes and values

In the fourth section, there was a question that asked about the importance of men and women being treated equally and enjoying the same opportunities; over 80% of respondents answered “important” or “very important.” Sorting by the strengths of respondents’ gender stereotypes, 70% of respondents with weak stereotypes answered that gender equality is “important,” while 10.9% of respondents with strong stereotypes said it is “neither important nor unimportant” and 3.4% said it is “not very important.” This indicates a tendency among those with strong stereotypes to place less emphasis on gender equality.

Thoughts and impressions

From what we have seen so far, it is evident that gender stereotypes are limiting our possibilities, but how can we solve this problem?

For detailed suggestions, I would like you to read the PIJ report, but here I hope we can consider solutions based on the comments made during the panel discussion.

During the panel discussion, some expressed the need for education at the early stages of a child’s development, as a significant number of children already have strong gender stereotypes.

I agree with the importance of early education, considering that, as a child, I myself thought it was better to be pretty than to achieve in academics because I was a girl. This will entail gender education for schoolteachers who may already have gender stereotypes.

At the same time, if we implement the kinds of education that high school students proposed, which is to recognize each other’s strengths so as to remedy the inclination to be concerned about others’ opinions of ourselves, I think children can become truer to their feelings and engage in what they really desire to do.

Through education for both children and teachers, it is my hope that we can realize a society where everyone can freely shine in their own way without being restricted by gender.

Original text by Haruka Nakaoda (JNPOC’s volunteer writer) originally posted on June 15, 2022; translated by JNPOC

Recent Articles

- Towards a society where children want to embrace life

- The Evolution of Philanthropy: Five approaches shaping contemporary practice

- 25 years of community understanding and moms’ hard work: The activities of Kinutama Play Village

- Connecting memories: Courage found at the film screening of parents’ legal battle after the Great East Japan Earthquake Tsunami

- An NPO project I came across while reflecting on teacher shortages after leaving my teaching job

- To unlock philanthropy’s potential for Japan, we need to understand its meaning