B4S Survey Report 1: The Reality of Children Living in Child Care Home in Japan Reports

Posted on June 21, 2016

By B4S (Bridge For Smile)

Youth living in Child care home practice cooking as the preparation to be independent before graduating from their child care home (Photo: Bridge for Smile)

28,000 Children Living in Childcare Homes. 60% Have Been Abused.

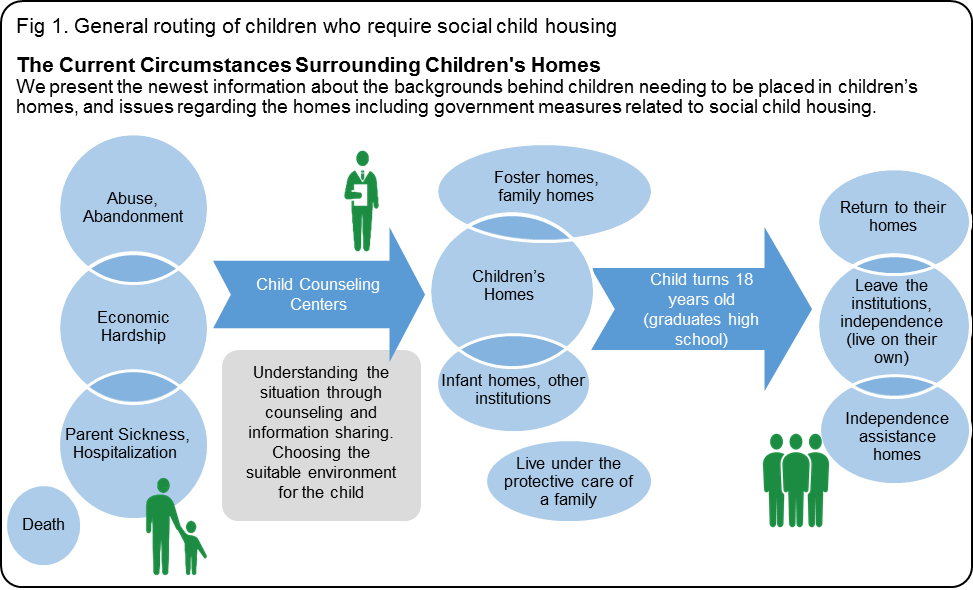

Children up to the age of 18 who are unable to stay under the care of their own parents are raised in children’s homes or foster homes overseen by the government. This proportion of children continues to be high, the current figure stands at 46,000 in Japan.

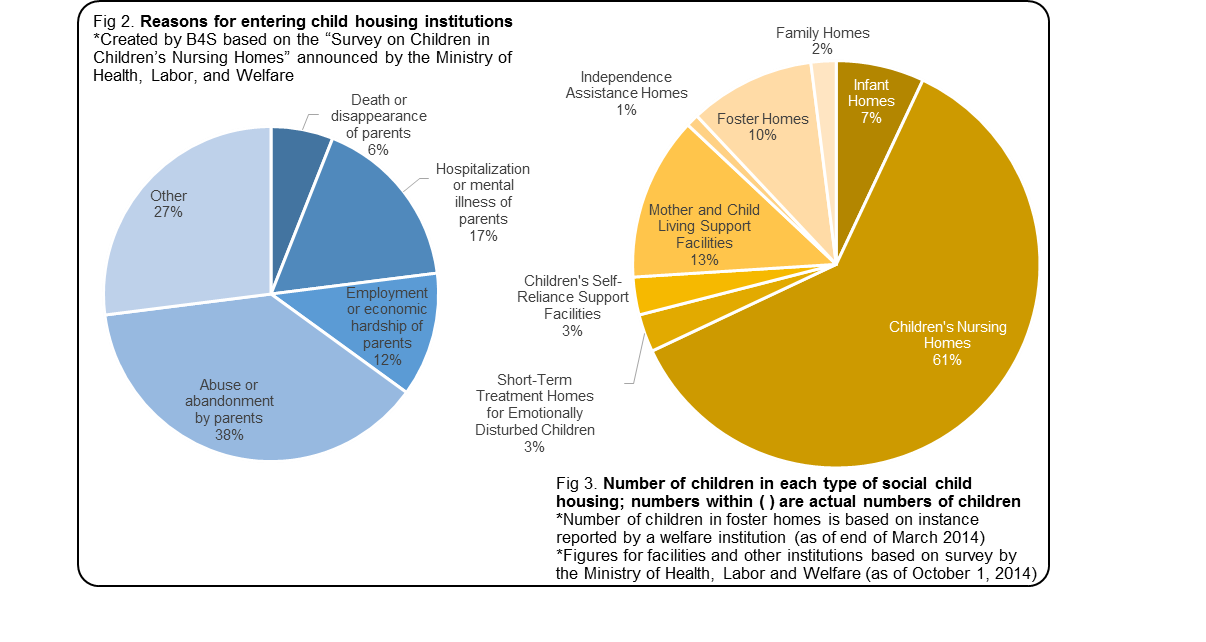

28,183 of these children are living in 601 children’s homes across Japan designed mainly for children from ages 2 to 18. Once commonly perceived as “orphanages”, these homes currently house more cases of children who face abuse, mental illness, hospitalization, or economic hardship of their parents, with only a minority 10% of the children who are there as a result of the death or disappearance of their parents. Among those reasons, children who are taken in because of abuse make up nearly 40%, of which 60% have been abused by their parents.

More than 80% of children living in these homes remain in contact with their parents after being admitted, either by telephone, visits by their parents to the homes, or trips by the children back to their own homes. The average length of stay in these children’s homes is 4.9 years, but 7% of them, around 2,100 children, spend 12 years or longer in the homes. This means there is a significant number of children who grow up without spending any of their childhoods living in an actual household.

Over 70,000 Reported Cases of Child Abuse Each Year

As society has become more concerned about child abuse, child counseling centers have continued to see an increasing number of abuse cases. In 2013, Japan had 73,765 reported cases of child abuse, 6.3 times more cases since Japan passed the Child Abuse Prevention Law in 2000. There has also been no decrease in the number of abuse cases resulting in deaths, with 51 deaths from abuse in 2012 and 39 children killed as part of double suicides.

Working Towards a Normal Home Environment

Being able to replicate the household setting is currently an important challenge for children’s homes. If the adult-to-child ratio can be reduced to a manageable number, children will be able to build deeper relationships with these adult staff and foster parents. This would translate into better physical health and mental stability in these children, which would facilitate their acquisition of life skills.

The number of homes with capacities of 20 children and above has decreased from 70% to 50% as the move to downsize them has picked up steam. Other alternative arrangements include “Small Group Care” where children within the same home are split into groups of six to eight, and “Group Homes” where groups of around six children to live together in a regular housing unit.

As the presence of children under the care of foster parents create an environment that most closely resembles an actual household life, Japan is moving to place more children into such settings. As of end March, 2014, there were 9,441 registered households, with 4,636 children living in a total of 3,560 households. Moreover, the number of “family homes” where foster parents take in at least two, and up to six, children has increased.

Although the proportion of beneficiaries living with foster parents or in “family homes” stand at just over 10%, there remains a huge disparity amongst the areas. While there are areas like Fukuoka city where the local government has stepped up efforts to increase fostering arrangements, there are regions like Niigata Prefecture observe a figure as high as 40.3% of children beneficiaries placed in foster homes, and others like Akita prefecture where the figure remains at 6.2% low.

Over the next 15 years beginning from fiscal year 2015, Japan aims to split these children evenly into the three arrangements, with one-third in “foster homes and family homes,” another third living in “group homes” and the remaining in “housing homes.” In view of the current lack of infrastructure for foster and family homes as well as manpower shortage, the hope is for sustainable government measures in bringing more people to support children after they have been assigned to the homes, and to spread information about the system.

Countries in Europe and North America have widely introduced adoption systems to give children the option of finding an adoptive home. A movement has also gotten under way in Japan to facilitate adoptions through child counseling centers and private organizations for identified cases where parents wish to disown their children, such as in unwanted pregnancies.

A Childcare home in Japan (Photo: Bridge For Smile)

Working to Build a Society Where “the Well-Being of Children” is the Highest Priority

A variety of systems are being created and revamped with the idea of making “the Well-Being of Children” the highest priority. The Law on Measures to Counter Child Poverty was enacted in January 2014. This specific initiative also includes measures such as after-care for children who have left the homes, and learning support for children who have not been able to study enough living in their own homes.

Starting in fiscal year 2012, a law was effected, making it clear that even parents cannot, unless with good reason, stand in the way of necessary measures put in place for their children. There have also been claims to enable child counseling centers to expropriate parental authority when parents refuse medical treatment for their children living in the children’s homes, or attempt to bring them back to households where sexual abuse has occurred.

The Child Poverty Act was created when the public eye reached out to children in single parent households and households on welfare that were struggling to live and to do their schoolwork.

We adults have the responsibility to support each and every child, in order to realize “A society in which children’s futures are not confined by the environments they were born into.”

About Bridge for Smile (B4S) and This Survey Report

Stated in its slogan, “it is our societal responsibility to enable children, forced into children’s homes by circumstances beyond their control, to find their dream, hope and place in society,” a Japanese nonprofit, B4S has been working on aiding children residing in children’s homes since its founding in 2004. The number of children receiving care from the children’s homes approximates at around 30,000 in Japan. These children, bearing emotional burdens, such as history of abuse and parents’ with poor health, are forced to match up to the expectations of society and be independent at the age of 18. At an age where most of their counterparts have the luxury of family support, they are left to face the harsh realities of society. In order to elucidate the situation faced by these children, B4S summarizes a report based on a survey conducted by the organization in 2014. The content in this report is entirely extracted from the Self-Reliance Support White Paper 2014 published by B4S.

* B4S is a grantee of Adobe Foundation (2011-2015) facilitated by Give2Asia, a partner of JNPOC.

Recent Articles

- Towards a society where children want to embrace life

- The Evolution of Philanthropy: Five approaches shaping contemporary practice

- 25 years of community understanding and moms’ hard work: The activities of Kinutama Play Village

- Connecting memories: Courage found at the film screening of parents’ legal battle after the Great East Japan Earthquake Tsunami

- An NPO project I came across while reflecting on teacher shortages after leaving my teaching job

- To unlock philanthropy’s potential for Japan, we need to understand its meaning