Rebuilding the foundations: how communities must address root causes for society’s outsiders, the homeless Part1 Tohoku Interview: Social Inclusion

Posted on December 07, 2015

by Kris Kosaka

Social inclusion: Empowering the isolated in local communities

A priority of social care within any society is the struggle to include the isolated: the disenfranchised, the disabled, the mentally ill, the elderly or the homeless. In the Tohoku area, over four years since the triple disasters of March 11th, the struggles for those living on the edge of society continues. With so many people within society still needing assistance, from the demands of temporary housing to rebuilding, from compensation issues to the dearth of medical professionals, how are the affected areas ensuring that the voiceless are being heard?

“Homeless” is emergency evacuation state, so we’ve always believed that the problems of the homeless can’t be solved without finding out the reason for poverty, as simply helping the homeless who came to the last stage cannot be the fundamental cure.” Seiji Imai

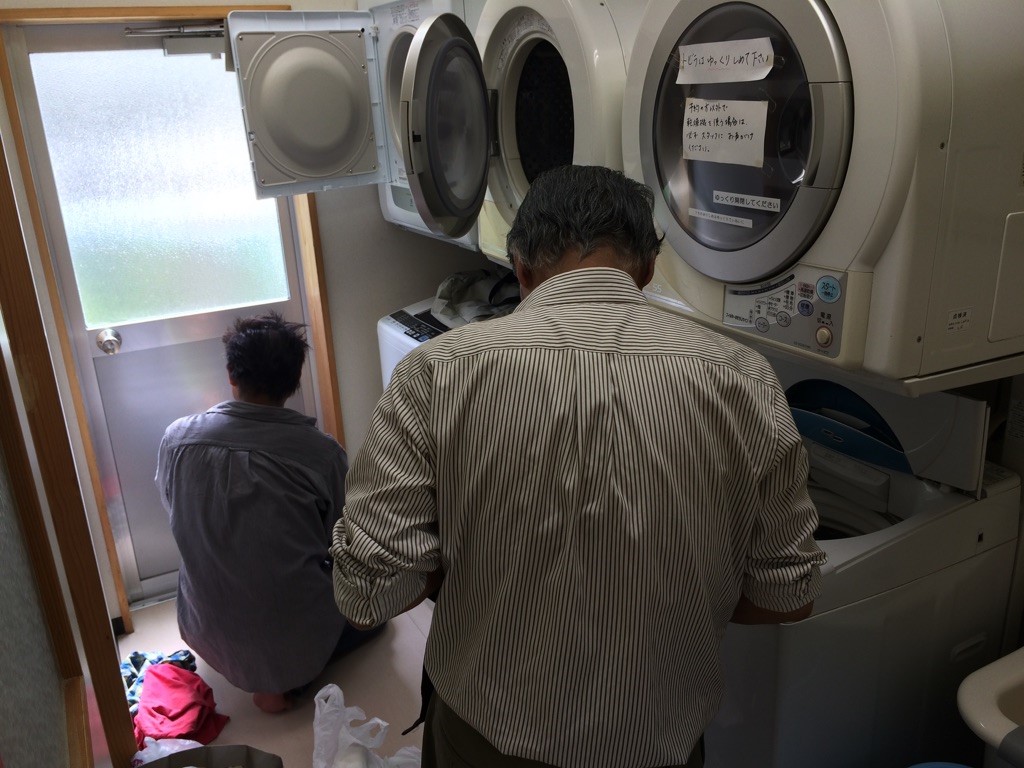

Yomawari offers the chance for a warm shower and a place to clean laundry

Yomawari offers the chance for a warm shower and a place to clean laundry

Yomawari (Sendai Yomawari Group) or “Night Patrol”, an NPO started in 2000 to support the homeless in the wider Sendai area, says their mission has not changed at all since the tragedy. Yomawari’s services include outreach support from soup kitchens or curry and rice in the park to job counseling; from offering community events or advice and training on life skills or battling addictions. With the increased stress of daily living after the disaster and the surge in the poverty-stricken coming to Tohoku in the hope of finding jobs in the aftermath, there is an increased demand for Yomawari’s work.

“Food Farm” enables participants to rediscover a rhythm of daily life while learning skills and engaging in disciplined tasks to use in future employment opportunities

“We’ve always tried to help the poorest of the poor and the weakest of the weak to get their lives back, explains Yomawari founder Seiji Imai. “One thing that has made a difference is much more attention has been drawn to our work because of the disaster. Also, things that went unnoticed before the disaster have been brought to light.” Yet with awareness came an increased demand for help. As Imai explains, “immediately after the disaster, there were a lot of new jobs doing clean-up and menial labor related to the evacuation shelters and temporary housing. People coming to Sendai to seek jobs had win-win partnerships with the local communities. But after the acute recovery period, job opportunities decreased, and many were forced to live on the streets.”

According to Imai, before the quake the average age of homeless in the Sendai area was 50-60. Most were male, with only 5% female. After the quake, the average age dropped to 45.5, reflecting the influx of outsiders hoping for work.

The affected town after the disaster on 3/11/2011, Watari-chou, Miyagi: After the tragedy, many who had been surviving on the edge of society in other areas of Japan traveled to Miyagi seeking jobs in the reconstruction, and ended up being forced to live on the street.

The affected town after the disaster on 3/11/2011, Watari-chou, Miyagi: After the tragedy, many who had been surviving on the edge of society in other areas of Japan traveled to Miyagi seeking jobs in the reconstruction, and ended up being forced to live on the street.

Imai sees the homelessness problem in Sendai as indicative of a wider social problem in Japan. “Homeless” is emergency evacuation state,” according to Imai, “so we’ve always believed that the problems of the homeless can’t be solved without finding out the reason for poverty, as simply helping the homeless cannot be the fundamental cure.” Research into homelessness statistics in Japan support his belief. Although a 2014 investigation by the Health and Welfare Bureau of Tokyo asserts that the number of homeless has steadily decreased in the metropolitan area, falling to 914 in their approximate investigation, Tom Gill, professor of social anthropology at the Faculty of International Studies at Meiji Gakuin University, believes the issue is much more complex. “If you’re studying homelessness in Japan, you have to compare the trends in the homeless population to the trends in the welfare population.” Gill admits the number of homeless nationwide has fallen since its peak in 2003 at an estimated 25,000 to just over 7,000 in the most recent survey, but the amount of people teetering on the edge of society and requiring welfare assistance has dramatically risen. “In the mid 1990’s, there were about 800,000 people on government assistance,” Gill explains. “Today there are over 2.2 million Japanese on livelihood protection welfare (seikatsu hogo). In twenty years, we’ve seen the numbers more than double, and you’re looking at a difference of more than 1.4 million people.”

Writer: Kris Kosaka

Reporter: Kris Kosaka and Yoshiko Ugawa (JNPOC)

Coordinator: Tohru Nishiguchi (JNPOC) Yoshiko Ugawa (JNPOC)

Special thanks to Tom Gill (professor of Social anthropology at the Faculity of International Studies, Meiji Gakuin University)

Sendai Yomawari Group is a grantee of the Japan Earthquake Local NPO Support Fund, with its donor the Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited

Sendai Yomawari Group (Japanese only)

Your comments and feedbacks: Contact Us

Recent Articles

- Towards a society where children want to embrace life

- The Evolution of Philanthropy: Five approaches shaping contemporary practice

- 25 years of community understanding and moms’ hard work: The activities of Kinutama Play Village

- Connecting memories: Courage found at the film screening of parents’ legal battle after the Great East Japan Earthquake Tsunami

- An NPO project I came across while reflecting on teacher shortages after leaving my teaching job

- To unlock philanthropy’s potential for Japan, we need to understand its meaning